Origin of the Cochin

It is generally accepted that the jungle fowl (Gallus gallus.) it the sole ancestor of origin of all refer to as domestic chickens. This is the Monophyletic origin. Put forward by Darwin (1868) on the basis, domestic fowls mated freely with G.gallus but rarely with others (Where these domestic fowls came from, is a totally different question) Progeny from these crosses were often fertile whereas mating from three other members of the Gallus family were rarely so (Though this is not completely discounted)

Having been a Warrant Officer and not a GENERAL during my time in the Forces, I do not take a GENERAL view on this matter. I would support the theory of F B Hutt,(Ph.D). In his book "Genetics of the Fowl" as he brings forward a more broad minded thought of how all fowl originated, this being the Polyphyletic Origin. This theory though not embracing the monophyletic theory, does not completely discount it, there is a second and as I see it, more reasonable explanation or idea how the huge Asiatic breeds such as Cochin, Malay fowl, Langshans and Brahmas, for that matter the Asils are very much similar in type to the earliest imported Cochins. The huge size and placid friendly nature of these breeds is very similar that we are lead to believe of the Dodo. So the second choice of view point of breed origin, is that these, and possibly the Mediterranean breeds, were always separate from the small, shy, flighty Jungle Fowl (Gallus.gallus) But unlike the Dodo, these huge breeds were saved from extinction by man domesticating them to harvest for eggs and meat. So being saved from the explorer men spreading new unfamiliar predators that would either steal eggs or kill the birds or both. They were saved from the same fate as the Dodo, by mans need to feed himself.

Early History of the Cochin

(Selected from Wrights book of Poultry, by S H Lewer)

Though less popular now than in years gone by, Cochins well deserve still to head the list of breeds in any book or class of poultry.

Independent of their own merits, which have doubtless fallen Into the background since the modern standard of breeding has impaired their utility as layers and table-fowls, they have been the chief progenitors of a whole family of poultry, justly valued for their useful qualities, and all alike founded on a ochin cross. And apart from even that, their introduction was the most memorable event that has ever happened in the poultry world : there has been nothing like it before or since. Previously, very few indeed except farmers kept fowl and those were only scrubs or mongrels ; and one or two shows which made attempts to attract public attention were only looked upon with a good natured contempt. In 1850 Cochins were exhibited at Birmingham and changed everything. Every visitor went home to tell tales of the new fowl that were as big as ostriches, and roared like lions, while were gentle as lambs ; and took to petting like tame cats or dogs, which could be kept anywhere even in a a garret,(Attic) The excitement grew, and even in the street outside the show was crammed, and Punch drew and wrote about the new birds; and before people new where they were, they were in the midst of a curious " Poultry-Mania" in the middle of the nineteenth century. That was in it's accute stage, and could not last; but the breeding and exhibition of poultry did, to such an extent, that ever since there has never lacked a market for a really good bird. And the Cochin did it all. He is, The Father of the poultry fancy. And none may dispute this place of honour.

Books of much pretension have traced the origin of this breed to some fowls imported 1843, which afterwards became the property of Queen Victoria, under the name of "Cochin China Fowls." As regards the fowls themselves this was a total mistake. A drawing was given in the Illustrated London News of that date, from which and the description it is manifest that they had absolutely no points of the Cochin at all, save perhaps yellow legs and large size. The shanks were long and bare, the heads d carried back instead of forward, the tail large and carried high, the back long and sloping to the tail, the eyes black the plumage close and hard. Of what we may call Malay blood they probably had a great deal; of Cochin blood none, or but some trace in a cross. one thing about them there was : these fowis were not only big, but they probably did really come from Cochin China, and from them and that fact came undoubtedly the name, Which vill now belong, while poultry breeding lasts, to another fowl that has no right to it at all.

The real Cochin stock first reached this Country in 1847, Mr. Moody, in Hampshire, and Mr. Alfred Sturgeon, of Gray’s, Essex, both receiving stock in that year. Mr. Moody’s, so far as we can learn, were inferior in character and leg feather to Mr. Sturgeon’s, but were very large and of the same broad type ; and all alike came from the port of Shanghae or its neighbourhood. The birds were undoubtedly Shanghaes, and had never been near Cochin China ; and for years attempts were made to put this matter straight. The first Poultry Book of Wingfield and J ohnson ( i 8 5 3) wrote of them as Shanghaes, and all American writers strove for the same name years after the attempt had been abandoned in England ; but it was no use. We never knew a case yet where facts struggled against a popular name, but the name won in the end, and so it was here. The public had got to know the new big fowls as Cochins, and would use no other word ; and so the name stuck, in the teeth of the facts, and holds the field to this day.

Mr. Sturgeon’s stock, with subsequent imports from Shanghae, has been the main source from which Cochins were bred in this country; America has had many independent importa tions. Mr. Punchard’s stock was mainly from Mr. Sturgeon, the latter keeping from choice the lemons and buffs, while Mr. Punchard had the dark birds which originated the partridgeS colour being very uncertain in the breeding of those days. The late Mr. Sturgeon gave, in 1853, this account of the origin of his stock :—

The history of my Cochins is a very absurd tale, and full of ill-luck or, perhaps, carelessness—a term for which ill-luck is often substituted. I got them in 1847, from a ship in the West India Docks. A clerk we employed at that time happened to go on board, and, struck by the appearance of the birds, bought them on his own responsibility, and at what I, when I came to hear of it, denounced as a most extravagant price—some 6s. or 8s. each ! Judge of my terror, after my extravagance, when I found a younger brother had, immediately on their arrival, killed two out of the five, leaving me a cockerel and two pullets ; nor was my annoyance diminished on hearing him quietly remark that they were very young, fat, and heavy, and would never have got any better ! The cock shortly after died, and beyond inquiring for another, which I succeeded in ob-taining shortly after the original died, together with a number of hens, which reached this country under peculiar circumstances, I person-ally took but little interest in them till the eve before their departure for Birmingham in 1850. Neither my brother nor myself, before we obtained these birds, had taken very particular interest in poultry, and why we came to prefer the light-coloured birds still remains a mystery to me ; but so it was, for to Mr. Punchard and to all others we parted with none but the smaller and darker-colour ed birds. I have often laughed at the dreadful passes my now famous breed has been reduced to, and the very narrow escapes it has had of utter extinction—first the attack of my brother already narrated ' • then the death of the cock ; and in the third year the desperate incursions of some mischievous greyhound puppies, who killed one morning, five young birds just as they were getting feathered, besides many more on different occasions. Our birds all came from Shanghae, and were feather-legged. It is to the cock of our second lot that I attribute our great success. I have had fifty others since, in four or five lots, but not a bird worthy of comparison with my old ones, or that I would mix with them.

Independent of their own merits, which have doubtless fallen Into the background since the modern standard of breeding has impaired their utility as layers and table-fowls, they have been the chief progenitors of a whole family of poultry, justly valued for their useful qualities, and all alike founded on a ochin cross. And apart from even that, their introduction was the most memorable event that has ever happened in the poultry world : there has been nothing like it before or since. Previously, very few indeed except farmers kept fowl and those were only scrubs or mongrels ; and one or two shows which made attempts to attract public attention were only looked upon with a good natured contempt. In 1850 Cochins were exhibited at Birmingham and changed everything. Every visitor went home to tell tales of the new fowl that were as big as ostriches, and roared like lions, while were gentle as lambs ; and took to petting like tame cats or dogs, which could be kept anywhere even in a a garret,(Attic) The excitement grew, and even in the street outside the show was crammed, and Punch drew and wrote about the new birds; and before people new where they were, they were in the midst of a curious " Poultry-Mania" in the middle of the nineteenth century. That was in it's accute stage, and could not last; but the breeding and exhibition of poultry did, to such an extent, that ever since there has never lacked a market for a really good bird. And the Cochin did it all. He is, The Father of the poultry fancy. And none may dispute this place of honour.

Books of much pretension have traced the origin of this breed to some fowls imported 1843, which afterwards became the property of Queen Victoria, under the name of "Cochin China Fowls." As regards the fowls themselves this was a total mistake. A drawing was given in the Illustrated London News of that date, from which and the description it is manifest that they had absolutely no points of the Cochin at all, save perhaps yellow legs and large size. The shanks were long and bare, the heads d carried back instead of forward, the tail large and carried high, the back long and sloping to the tail, the eyes black the plumage close and hard. Of what we may call Malay blood they probably had a great deal; of Cochin blood none, or but some trace in a cross. one thing about them there was : these fowis were not only big, but they probably did really come from Cochin China, and from them and that fact came undoubtedly the name, Which vill now belong, while poultry breeding lasts, to another fowl that has no right to it at all.

The real Cochin stock first reached this Country in 1847, Mr. Moody, in Hampshire, and Mr. Alfred Sturgeon, of Gray’s, Essex, both receiving stock in that year. Mr. Moody’s, so far as we can learn, were inferior in character and leg feather to Mr. Sturgeon’s, but were very large and of the same broad type ; and all alike came from the port of Shanghae or its neighbourhood. The birds were undoubtedly Shanghaes, and had never been near Cochin China ; and for years attempts were made to put this matter straight. The first Poultry Book of Wingfield and J ohnson ( i 8 5 3) wrote of them as Shanghaes, and all American writers strove for the same name years after the attempt had been abandoned in England ; but it was no use. We never knew a case yet where facts struggled against a popular name, but the name won in the end, and so it was here. The public had got to know the new big fowls as Cochins, and would use no other word ; and so the name stuck, in the teeth of the facts, and holds the field to this day.

Mr. Sturgeon’s stock, with subsequent imports from Shanghae, has been the main source from which Cochins were bred in this country; America has had many independent importa tions. Mr. Punchard’s stock was mainly from Mr. Sturgeon, the latter keeping from choice the lemons and buffs, while Mr. Punchard had the dark birds which originated the partridgeS colour being very uncertain in the breeding of those days. The late Mr. Sturgeon gave, in 1853, this account of the origin of his stock :—

The history of my Cochins is a very absurd tale, and full of ill-luck or, perhaps, carelessness—a term for which ill-luck is often substituted. I got them in 1847, from a ship in the West India Docks. A clerk we employed at that time happened to go on board, and, struck by the appearance of the birds, bought them on his own responsibility, and at what I, when I came to hear of it, denounced as a most extravagant price—some 6s. or 8s. each ! Judge of my terror, after my extravagance, when I found a younger brother had, immediately on their arrival, killed two out of the five, leaving me a cockerel and two pullets ; nor was my annoyance diminished on hearing him quietly remark that they were very young, fat, and heavy, and would never have got any better ! The cock shortly after died, and beyond inquiring for another, which I succeeded in ob-taining shortly after the original died, together with a number of hens, which reached this country under peculiar circumstances, I person-ally took but little interest in them till the eve before their departure for Birmingham in 1850. Neither my brother nor myself, before we obtained these birds, had taken very particular interest in poultry, and why we came to prefer the light-coloured birds still remains a mystery to me ; but so it was, for to Mr. Punchard and to all others we parted with none but the smaller and darker-colour ed birds. I have often laughed at the dreadful passes my now famous breed has been reduced to, and the very narrow escapes it has had of utter extinction—first the attack of my brother already narrated ' • then the death of the cock ; and in the third year the desperate incursions of some mischievous greyhound puppies, who killed one morning, five young birds just as they were getting feathered, besides many more on different occasions. Our birds all came from Shanghae, and were feather-legged. It is to the cock of our second lot that I attribute our great success. I have had fifty others since, in four or five lots, but not a bird worthy of comparison with my old ones, or that I would mix with them.

Zum Bearbeiten hier klicken.

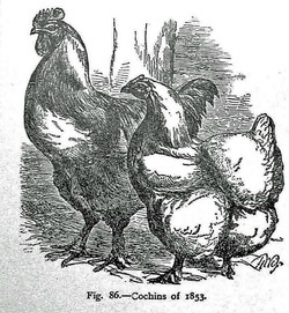

Mr. Sturgeon priced his first Cochins at Birmingham at £5 per bird, as a prohibitive price ; but Mr. Punchard deemed that sum ridiculously extravagant, and entered his at per pen of three. According to an account given by Mr. Sturgeon to Mr. Norris-Elye,* Mr. Punchard's pens were all claimed, , and Mr. Sturgeon's would have been also over and over again, but the would-be buyers waited in the supposition that he would take less, as Mr. Punchard's were so much lower in price. Mr. Sturgeon was thus enabled to claim the entire lot, and keep them in his own hands ; and a year or two later, when he had a sale—the first poultry sale of the kind ever held which was conducted by Mr. Henry Stafford, the late well - known Shorthorn auctioneer and the publisher of the Shorthorn Herd-book, his surplus stock of 120 birds realised a net total of L-609. The Cochins thus introduced into England were perceptibly dif-ferent from the present type of bird, though exhibiting in the main the chief character-istics which distin-guish them still in the broader features from other races of fowls. The accompanying illustration, which is reduced from a draw-ing by the late Mr. Harrison Weir in the Illustrated London News of 1853, will show the char-acters of the birds after they had settled down a little from a year or two of ex-hibition. There will be remarked in this contemporary drawing the globular masses of fluff over the hen's cushion and the thighs of both sexes ; the short and soft tail ; the moderately feathered shanks ; the medium-sized single comb ; the low and for-ward carriage ; the short legs set wide apart. Yet there is one difference of a marked character, apart from the, less amount of shank-feathering and absence of vulture-hock. The fluffy masses of the hen stand out in even more globular pro-tuberance than they do to-day ; and considering this further, we observe that the plumage of the fore-part of the body in both sexes is more tight and close-fitting than now, and hence this appears smaller in proportion to the hinder-parts. The difference is due more to plumage than anything else, for Mr. Sturgeon, writing in the same year, insists on "great depth from the base of the neck to the point of the breast-bone," and also on length of the latter. To this comparatively greater closeness of plumage over the forward portions of the body, while the hinder parts only were covered with deep fluff, we now know was due the greater laying powers of the Cochins of those days.

One or two other details about these early Cochins are very interesting. Mr. Sturgeon wrote (of buffs) even in 1853, that "the eye should be red and full," since it had already been found that "in all cases of contracted pupil and blindness, the pearl or broken-eyed birds have been the sufferers." This weakness of the pearl and This weakness and even of light yellow, still remains. The early birds also bred most amazingly in regard to colour, and the finest of the early blacks were bred from a white cock and buff hen. From one brood of ten chickens of this cross, two pullets were pure black ; two pullets and three cockerels black, with more or less gold in hackles, and marked wings ; the other three darkly pencilled birds. Another breeder put a buff cock with dark partridge hens ; the pullets from this cross were all light fawns. It has already been noted that Mr. Punchard's partridges were originally selected from the same stock as Mr. Sturgeon's buffs, one breeder prefcrring- the light and the other the darker colours. To the same mixture of colours is in doubt due the number of varieties recognised separately described.

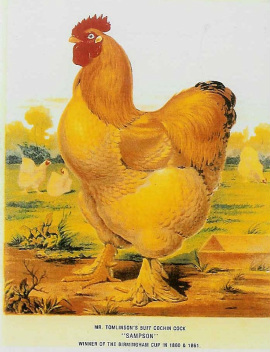

Ten or twelve years did not make much change in the general characteristics of Cochins yet a little is observable, as will be seen from the accompanying drawings made in 1865 by M. Jacque, the leading French poultry artist of that day. Though the head is ill-drawn, the cock here shows more " type " than the 1853 drawing, being more like the Cochin as we know it ; and both birds show more softness and looseness of feather ove7 the whole of the body than in the original type. It is this latter change which was to proceed so much further in later years, as shown very strongly in our plates of today, and reaching its climax, perhaps, in the American Cochin as now bred. The last marked change which took place was the admission of vulture-hocks, due to the passion for heavy shank-feather, together withmost inconsistent conduct on the part of the then leading judges. These had carried practical disqualification for vulture-hocks to such an extreme, that birds with the least fulness of shank-feather were repeatedly passed over for what was really only nice covering with quite soft and well-curled feathers. That pro-voked reaction to excessive shank-feather, and birds were exhibited with hocks heavily plucked; and then almost of a sudden the judges gave way and went to the other extreme, and vulture-hocks sprang in with a bound, so far as England was concerned. It always seemed to us that heavy and stiff quill-feather was inconsistent with the idea of a Cochin ; and it has been proved in America that heavy shank-feather can be bred without stiff hocks ; but in England the hocked fashion has now prevailed since about 1875. As the Cochin, with this and other changes, has now become almost entirely a " fancy fowl, kept up by fanciers solely, nothing can be said in objection to the standard they adopt ; but the few birds now exhibited in comparison with the large classes which formerly appeared at large shows,* are an eloquent testimony to the change which has taken place in general appreciation of this once popular breed.

Ten or twelve years did not make much change in the general characteristics of Cochins yet a little is observable, as will be seen from the accompanying drawings made in 1865 by M. Jacque, the leading French poultry artist of that day. Though the head is ill-drawn, the cock here shows more " type " than the 1853 drawing, being more like the Cochin as we know it ; and both birds show more softness and looseness of feather ove7 the whole of the body than in the original type. It is this latter change which was to proceed so much further in later years, as shown very strongly in our plates of today, and reaching its climax, perhaps, in the American Cochin as now bred. The last marked change which took place was the admission of vulture-hocks, due to the passion for heavy shank-feather, together withmost inconsistent conduct on the part of the then leading judges. These had carried practical disqualification for vulture-hocks to such an extreme, that birds with the least fulness of shank-feather were repeatedly passed over for what was really only nice covering with quite soft and well-curled feathers. That pro-voked reaction to excessive shank-feather, and birds were exhibited with hocks heavily plucked; and then almost of a sudden the judges gave way and went to the other extreme, and vulture-hocks sprang in with a bound, so far as England was concerned. It always seemed to us that heavy and stiff quill-feather was inconsistent with the idea of a Cochin ; and it has been proved in America that heavy shank-feather can be bred without stiff hocks ; but in England the hocked fashion has now prevailed since about 1875. As the Cochin, with this and other changes, has now become almost entirely a " fancy fowl, kept up by fanciers solely, nothing can be said in objection to the standard they adopt ; but the few birds now exhibited in comparison with the large classes which formerly appeared at large shows,* are an eloquent testimony to the change which has taken place in general appreciation of this once popular breed.